The Black Law Students Association (BLSA) at the University of Virginia School of Law was founded fifty years ago, on October 16, 1970, out of a need to collectively voice the concerns of Black law students. At the time, UVA Law was housed in Clark Hall on Central Grounds, the Law faculty was comprised almost entirely of white men, and there were very few women and Black students, though their numbers were increasing. One year earlier, in 1969, the largest number of Black students in one class—13 out of a total of 341—entered the Law School. This pivotal year, amid the Civil Rights Movement and in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., provided the urgent and necessary moment for BLSA’s founding.

Integration at UVA Law

The Civil Rights Movement swept the nation in the 1960s, with new legislation and activism to address longstanding issues of institutional racism and injustice. UVA Law and the legal profession more broadly, however, remained predominantly white. Nationally, for most of the 1960s, Black law students made up only 2% of annual American law school graduates. UVA Law showed similar numbers: in 1971, Black enrollment at the Law School was 3%, a mere 28 students among the 900 enrolled. With no steady institutional commitment to address this racial imbalance, change at UVA Law was slow in coming.

Black student enrollment at UVA Law had increased only marginally since Gregory Swanson, an attorney from Danville, Virginia, first integrated the University in 1950. That year, Swanson sued for and won admission to the Law School and was the first Black student at the Law School and the University. Swanson’s application was initially accepted by the UVA Law faculty but later denied by the UVA Board of Visitors, leading Swanson to take his case to court.

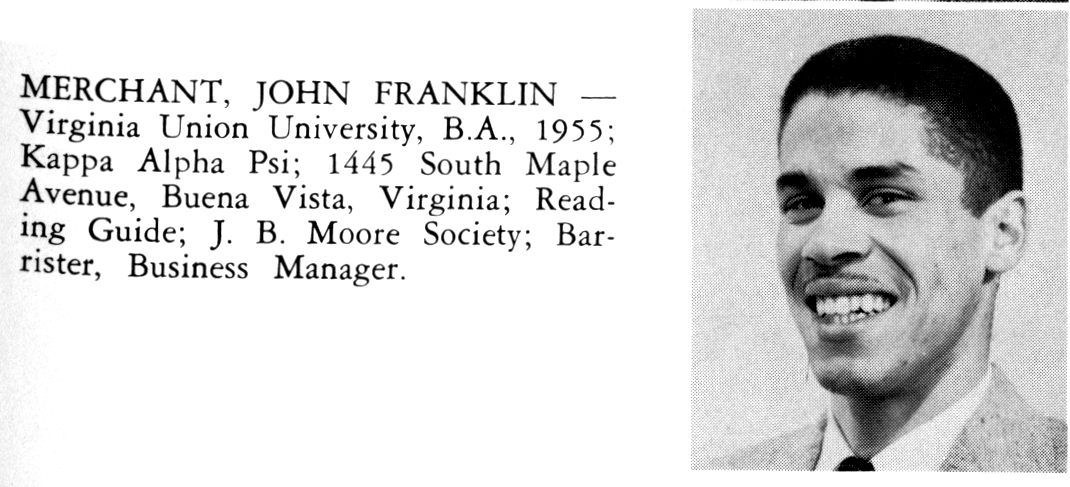

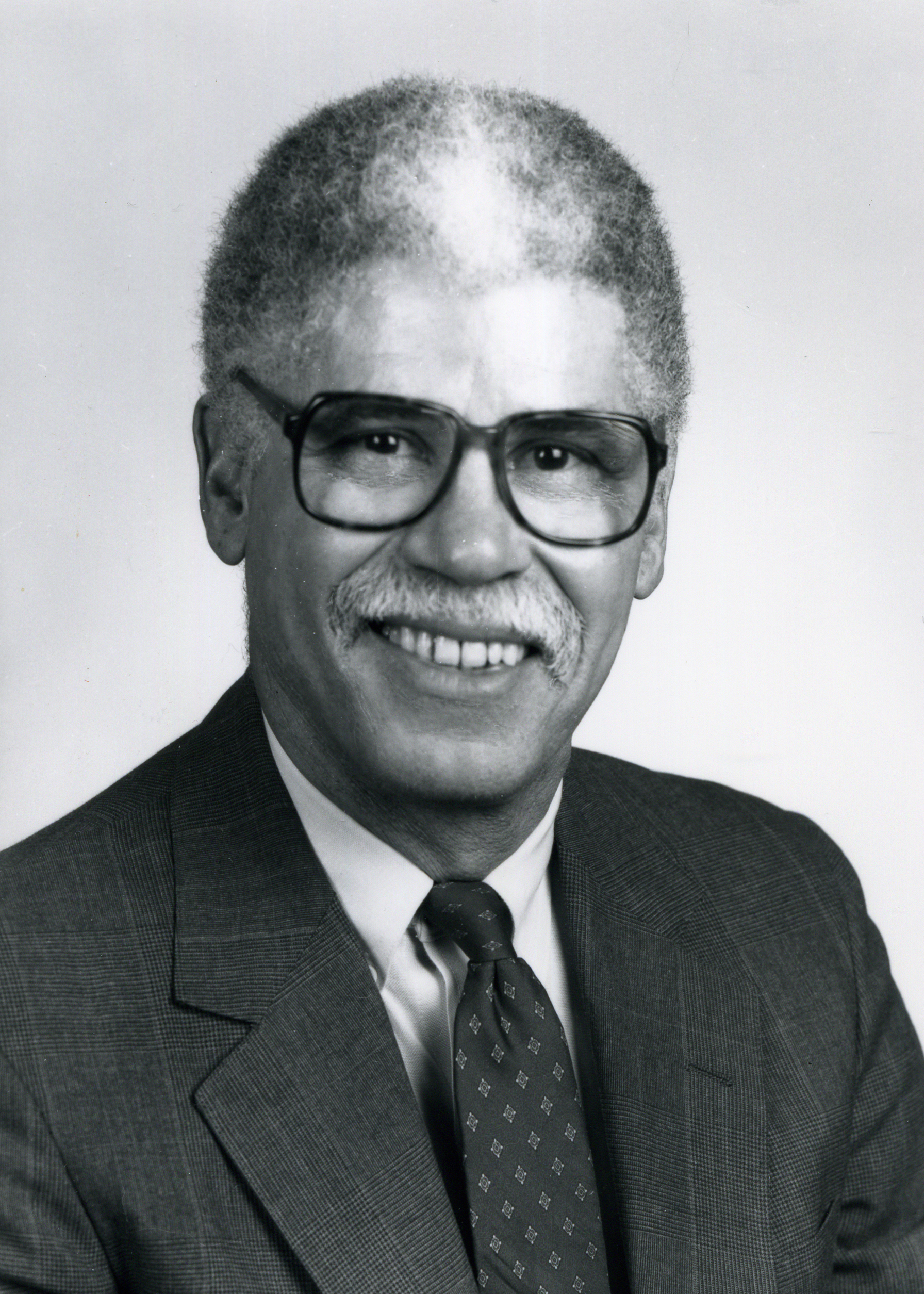

Eight years later, John Merchant ’58 became the first Black student to graduate from UVA Law. In 1967, Elaine Jones became the first Black woman to attend UVA Law. When she graduated in 1970, Jones was only the ninth Black student to graduate from the Law School since Swanson’s matriculation in 1950.

Jones was one of two Black students in her class, and one of five Black students at the Law School at the time. While the Law faculty adopted a new admissions policy in 1967 encouraging minority enrollment, Jones recalled that the University did not entirely feel like a “welcoming environment.”

In 1968, just one year after Black Americans celebrated Justice Thurgood Marshall's nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. That day at UVA Law, Jones recalled that no one even mentioned King’s death. To her, the silence signified the covert, “environmental” discrimination of African American students at UVA:

“I came to school that day... no one said a word. Not a student, not a professor, no one said one word. Nothing. And at the end of the day I went to Jimmy [James Benton, Jr. ’70]—who was the other Black person in my class—and I said ‘Jimmy, do they know? Do they know?’ Of course they knew. Of course they knew, but in many of their minds King was a rabble-rouser.”

At New York University, King’s 1968 assassination galvanized Black law students to form the nation’s first Black American Law Student Association (BALSA, now BLSA). Chapters across the country, including at UVA, would follow soon thereafter.

"It was almost like somebody said,

‘Brothers and sisters, what are you going to do now?’"

Robert Holmes

NYU Law student and founding member of the country's first BALSA chapter, on the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Class of 1972

Thirteen Black law students arrived at UVA in the fall of 1969, the largest entering class of Black students in UVA Law’s history to that point. Although constituting less than 4% of their class, these 13 students asserted their voice and quickly organized with the rest of the Black law student population to form UVA’s own BALSA chapter.

This record Black enrollment at the Law School came about in part through new recruitment programs by Law administration and enrolled Black students.

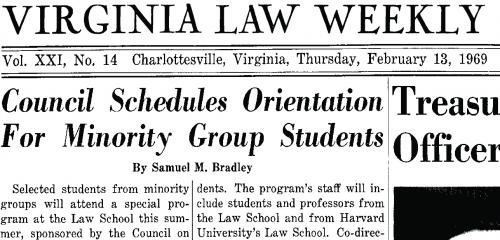

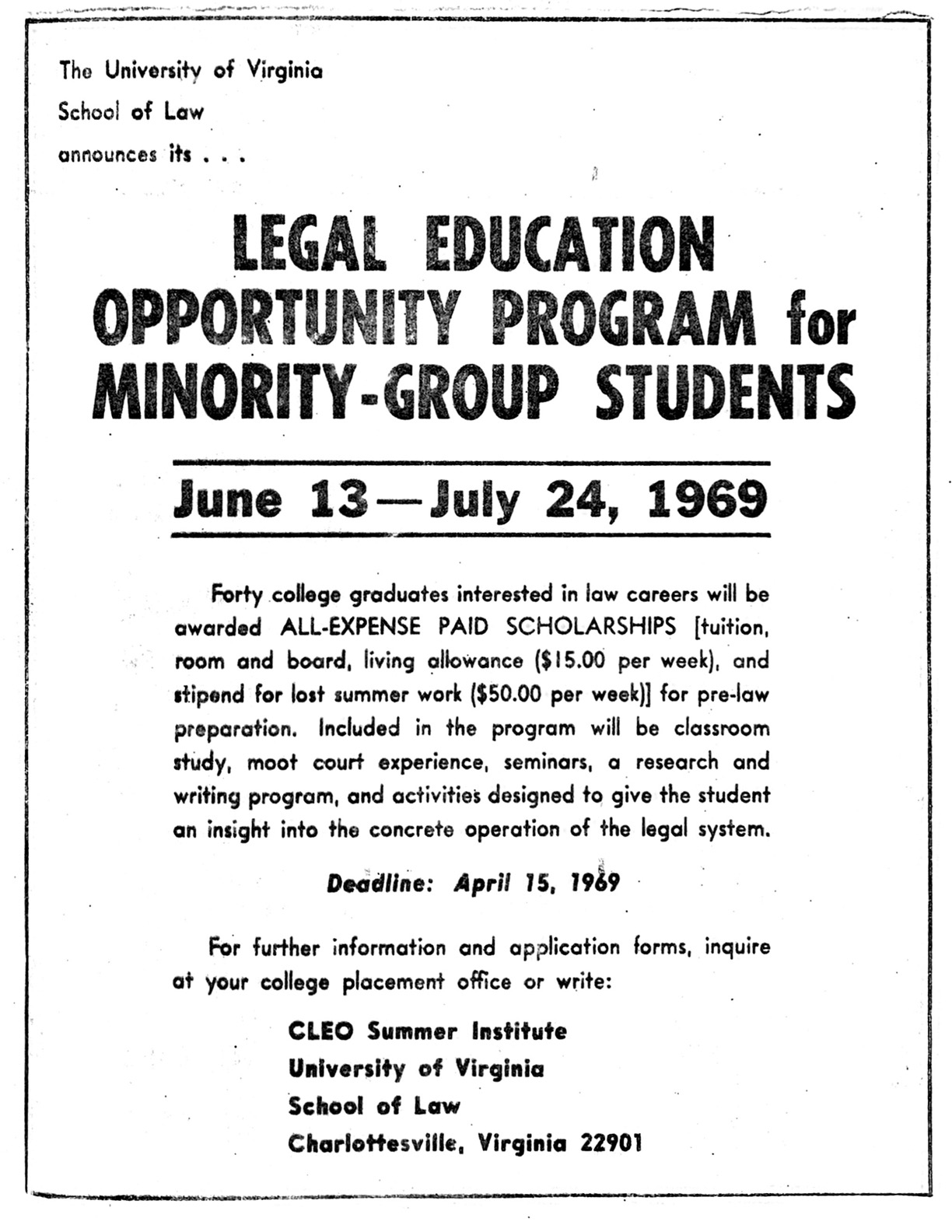

In the summer of 1969, UVA Law hosted a Council of Legal Education Opportunity (CLEO) summer institute for 40 pre-law students from minority backgrounds to provide early legal training and insight into law school life, with the ultimate goal of increasing minority law student enrollment in law schools.

Elaine Jones ’70 and James Benton ’70 served as teaching assistants during the six-week program. At the program’s completion, all 40 students were offered admission to a law school. Ten students in the cohort were offered admittance to UVA Law, and nine of the ten matriculated in the fall of 1969.

In the 1960s, people of color made up roughly 2% of the legal profession. CLEO took shape in 1968 to address this discrepancy. Inspired by successful “pre-start” programs at Harvard, Emory, and elsewhere, the American Bar Association, the Association of American Law Schools, the Law School Admission Council, and the National Bar Association collaborated to form CLEO. The program would sponsor additional institutes and provide law school tuition funding. Grants from the Office of Economic Opportunity and the Ford Foundation would fund the first two years of law school for CLEO participants, which ensured the accessibility of the program. Law schools were then expected to provide funding for the third year.

“I was selected to participate in the CLEO Program at UVA, along with 30-some other students. And so that gave UVA and me a chance to check each other out. I had actually accepted an offer at Rutgers. But then, toward the end of the program, UVA told me I’d been accepted.”

—Bobby N. Vassar ’72, BALSA Convener 1971-1972, in a 2020 interview for the UVA Lawyer.

The students from UVA’s CLEO program naturally became close. This bond played a role in unifying what was, at the time, UVA Law’s largest entering class of Black students. BALSA founder Bobby Vassar ‘72 was one of the nine students admitted through CLEO.

During the 1968-1969 academic year, the Law administration also expanded student recruitment trips to include Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Black student participation in these trips was imperative to their success. That year, Black students and Law professors visited Fisk University, Hampton Institute, Howard University, Morgan State, Norfolk State, North Carolina Central University, Shaw University, Virginia State University, and Virginia Union University.

Elaine Jones ’70 accompanied Professor Charlie Whitebread to Hampton Institute in Virginia. At Hampton, Jones and Whitebread met with Jones’ sister, Gwendolyn Jones Jackson, who served as Vice President of the Women’s Senate and was on her way to graduating cum laude with a degree in English. With her impressive credentials, the pair convinced Jackson to apply to UVA Law. She joined the incoming Law class the following fall.

“I determined that law is a more immediate means by which to improve the human condition and erase many of society’s ills.”

Gwendolyn Jones Jackson ’72

Quoted in New Journal and Guide, 17 January 1970

Building Momentum

With a strengthened and unified voice, UVA Law’s Black students asked new questions of Law administration and demanded accountability for longstanding issues that they believed deserved urgency of action.

Of immediate concern: UVA Law did not have a single Black professor.

On October 9, 1970, the Law Weekly published a short article announcing that the Law Student Council passed a resolution “endorsing the appointment of blacks to faculty of the School of Law of the University of Virginia.” Paul Garrett ’71 had proposed the resolution on behalf of the rest of the Black law students, stating that the Law School had an obligation to hire Black professors and that Black professors would benefit the entire student body.

The faculty’s Appointments Committee responded to Student Council’s resolution with an assurance that the committee was “continuing to search actively for black lawyers who may qualify.”

This faculty response frustrated the Black student body, but it was an anonymous op-ed in the same Law Weekly issue that was the last straw. In an editorial titled “Black Professors…” a student author supported the Law Council’s recent resolution but claimed that the administration could not improve their search for Black faculty because there were no qualified Black candidates who met the criteria expected of white faculty. After arguing that Black law students had been admitted according to “dual,” or less rigorous, criteria relative to their white peers, the author stated that considering race for hiring a faculty member would necessarily require lowering hiring standards and would, therefore, be deleterious to the education of the entire student body.

UVA’s Black law students published a response to the editorial in the Law Weekly a week later. They described the “Black Professors” article as “an inaccurate, retrogressive, uninformed, ill-reasoned voicing of liberal ideology actually undergirded by prejudiced attitudes” and “an insult to every competent Black lawyer, every Black alumnus of The Virginia Law School, and to those Black law students presently enrolled here.” The students argued that they did not claim that skin color should be the sole requirement for faculty hiring, rather, the administration appeared to have “amorphous criteria” for faculty hiring that failed to explain why the Law School had yet to hire a Black professor when there were eligible candidates in the state.

The students then addressed the issue of “dual standards,” qualifying that “the establishment of a dual standard does not a priori reflect use of less stringent criteria.” To claim that dual standards implied looser criteria was to claim that Black students were somehow “inferior” to their white counterparts.

The authors concluded:

“At Virginia, we need a change of heart, a firmer and less rhetorical commitment to equal opportunities which will be reflected by the hiring of Black law professors here in the halls where justice is taught.”

1970: Founding BALSA

On October 16, 1970—the same day the Law Weekly published the Black law students’ response to the editorial “Black Professors” —UVA Law’s Black students founded their own BALSA chapter.

BALSA’s first officers were Albert L. Preston ’71, Convener; Gloria H. Bouldin ’73, Secretary; Leonard McCants ’72, Chairman of Public Relations; Gwendolyn L. Jones ’72, Chairman of Admissions; S. Delacy Stitch ’72, Chairman of Finance; Jack W. Gravely ’72, Chairman of Community Relations; and Bob N. Vassar ’72, Chairman of Curriculum.

“We were trying to increase the numbers, obviously, of Black students.

But we wanted the Law School to hire a Black professor. So I think we wanted a unified approach, an advocacy position, as a group.”

Margaret Poles Spencer ’72

BALSA Historian 1971-1972

In the Law Weekly’s first article regarding BALSA, the editors paraphrased McCants’ explanation for the organization’s founding, writing that the “formation of BALSA was not a response to any one occurrence at the Law School or University, but rather the result of a long-growing awareness of a need for direction among Black students.”

The organization drafted a constitution and bylaws, which outlined the group’s structure of committees and officers, as well as the underlying reason behind its formation. In a mid-1970s copy of the constitution, BALSA’s mission statement read:

“Recognizing the need for an effective organization to represent the views of the Black students of the University of Virginia Law School, the Black students of the University of Virginia Law School do hereby establish the Black American Law Student Association of the University of Virginia.”

BALSA’s initial goals, which remain in place today, were to recruit Black law students and faculty, open a candid forum between UVA Law’s Black and non-Black students, assist underserved populations in the Charlottesville community, and facilitate inter-school communication between other BALSA chapters.

Article XII, the final article of the constitution, simply stated:

"Let's get it together."

BALSA's Minority Recruitment Efforts

UVA’s newly formed BALSA chapter jumped quickly into its work.

On the weekend of December 11, 1970, BALSA hosted a Minority Pre-Law Conference at Clark Hall. Collaborating sponsors included CLEO, the Law Students Civil Rights Research Council at UVA, and thirty law schools in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions. Assistant Dean Albert Turnbull encouraged Law faculty to attend.

Activities included speeches and panels concerning minority groups’ roles in the legal profession, networking opportunities, and a banquet. Seventy-five Black college students attended.

To bolster minority recruitment, BALSA members visited colleges up and down the East Coast to persuade undergraduates to consider UVA Law. Since tuition was a major recruitment deterrent, BALSA members also lobbied Law administration for increases in financial aid and scholarships.

1972: Diversifying the Faculty

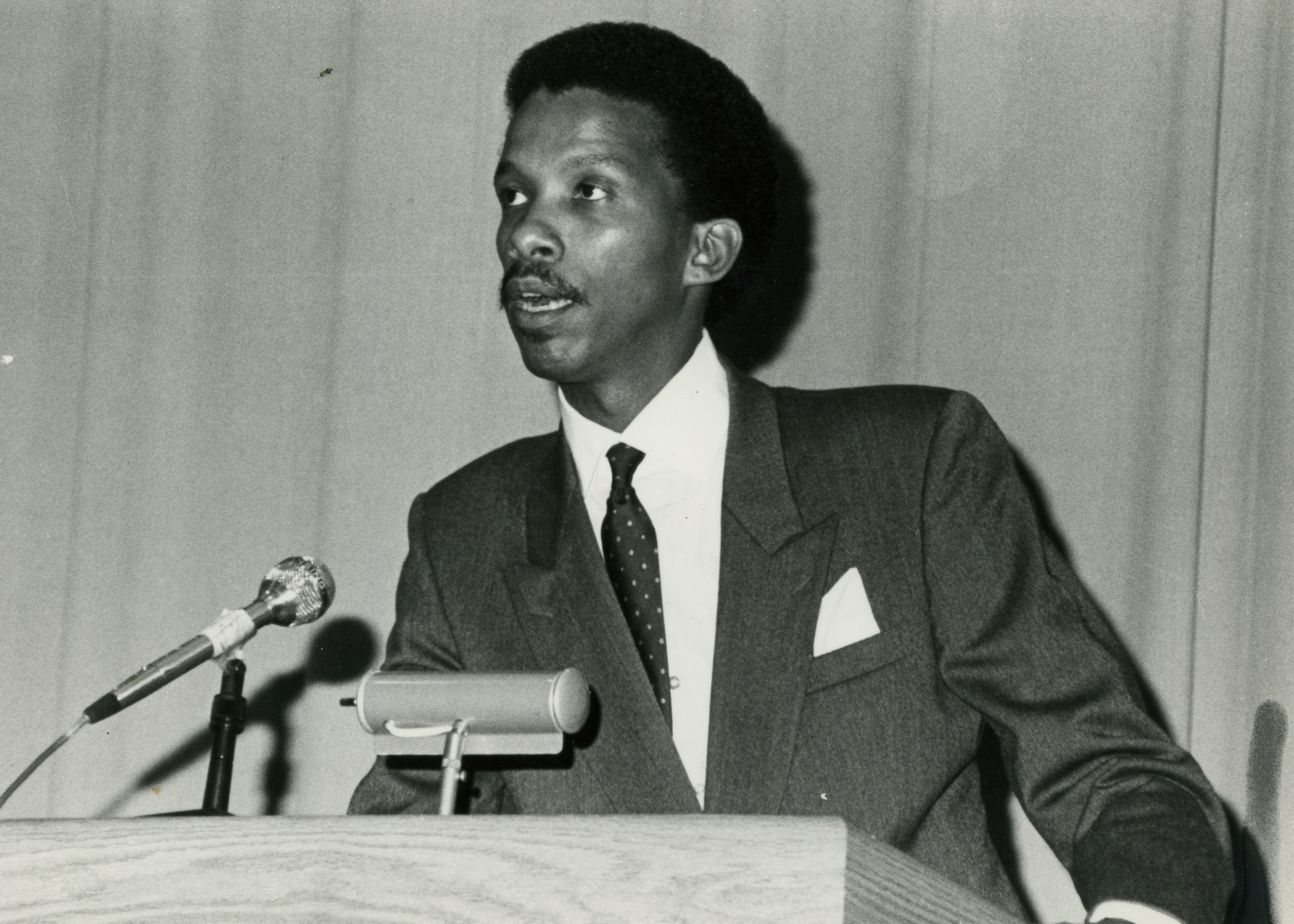

As BALSA celebrated the success of the Pre-Law Conference, the group simultaneously pushed Law administration to double down on faculty hiring efforts. In March 1972, BALSA held a press conference in Clark Hall to announce the organization's new resolution on appointing Black lawyers to the Law faculty.

On the heels of BALSA’s multi-year campaign to convince Law administration to expedite the hiring of a Black faculty member, frustration with a lack of results had brought the issue to a head. In the spring of 1971, there were two Black lecturers at the Law School, but no full-time, permanent Black faculty. That fall, McCants and the Law Student Council formed an ad-hoc committee for the recruitment of Black professors, which proposed a resolution to allow student representatives to serve on the faculty’s Appointments and Tenure Committee. The resolution did not pass.

“We endeavored to do a systematic approach to challenging the University on its failure to have Black faculty.”

—Bobby N. Vassar ’72, BALSA Convener 1971-1972

As UVA’s Black law students pressed Law administration to publicize their hiring strategies, administrators claimed that there simply were not enough eligible Black candidates, and those who were eligible were not interested in leaving their current positions in private practice to teach. In response, BALSA drafted a list of fifty eligible Black lawyers in the fall of 1971 and sent it to the faculty.

In the spring of 1972, BALSA sent a survey to the faculty, and about 80% confirmed that they did want to hire Black attorneys. The administration again claimed that there were few eligible Black attorneys who wanted to teach. BALSA responded that UVA Law was limiting itself by only reaching out to peers at the most elite law schools, who in turn were trying to diversify their faculty. BALSA noted that the Law School appeared to have no problem hiring young white lawyers to the faculty that had “little more credentials than their law school grades,” and questioned why Black faculty members had to be a “super candidate.”

“[The Law School has] failed to implement the mandate of justice, of its students and of its faculty by not appointing Black lawyers to the faculty.”

—1972 BALSA Statement on Faculty Hiring

In March, BALSA convened in Clark Hall to announce their request for a federal civil rights investigation and to address the press. A few days before, the organization had also sent letters to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, the United States Civil Rights Commission, Virginia Governor Lynwood Holton and UVA President Edgar Shannon.

In their statement to the press, BALSA recounted their efforts since the fall of 1969 to assist the faculty in hiring Black professors. The organization listed five actions the Law School must take to “remedy its negligence:”

- Appoint competent Black lawyers to the faculty for the next academic school year,

- Allow the active participation of BALSA in the selection of Black professors,

- Allow BALSA representation on the Committee on Appointments and Tenure,

- Report to the students regularly on its efforts in the area of employment of Black professors, and

- Refuse to make any further appointments to the faculty until competent Black lawyers are appointed to the faculty.

BALSA concluded by stating: “The difficulty of the task should not be used to excuse the lack of results, but should be used to determine the degree of commitment and dedication needed to produce results.” The very next day, BALSA was informed that Dean Monrad Paulsen had reached out to Larry Gibson, a Black lawyer from Baltimore who had taught a class at UVA Law in the fall, to teach full-time during the upcoming academic year.

Professor Gibson’s hire was a victory, but just two years later Gibson left UVA to accept a faculty position at the University of Maryland School of Law. As BALSA expanded their efforts and activities each year, the organization remained vocal about the importance of Black faculty not only to serve as mentors for Black law students, but also to broaden the perspectives of UVA Law’s student body. The lack of Black faculty would again come to the forefront of BALSA’s activist efforts in the 1980s.

“It made me feel that at least we had accomplished a small step in the right direction.

We felt that, but for our advocacy, but for the work we had engaged in to convince the Law School that this was wrong, Gibson would not have been hired. We opened their eyes to the value of diversity.”

Margaret Poles Spencer ’72

BALSA Historian 1971-1972

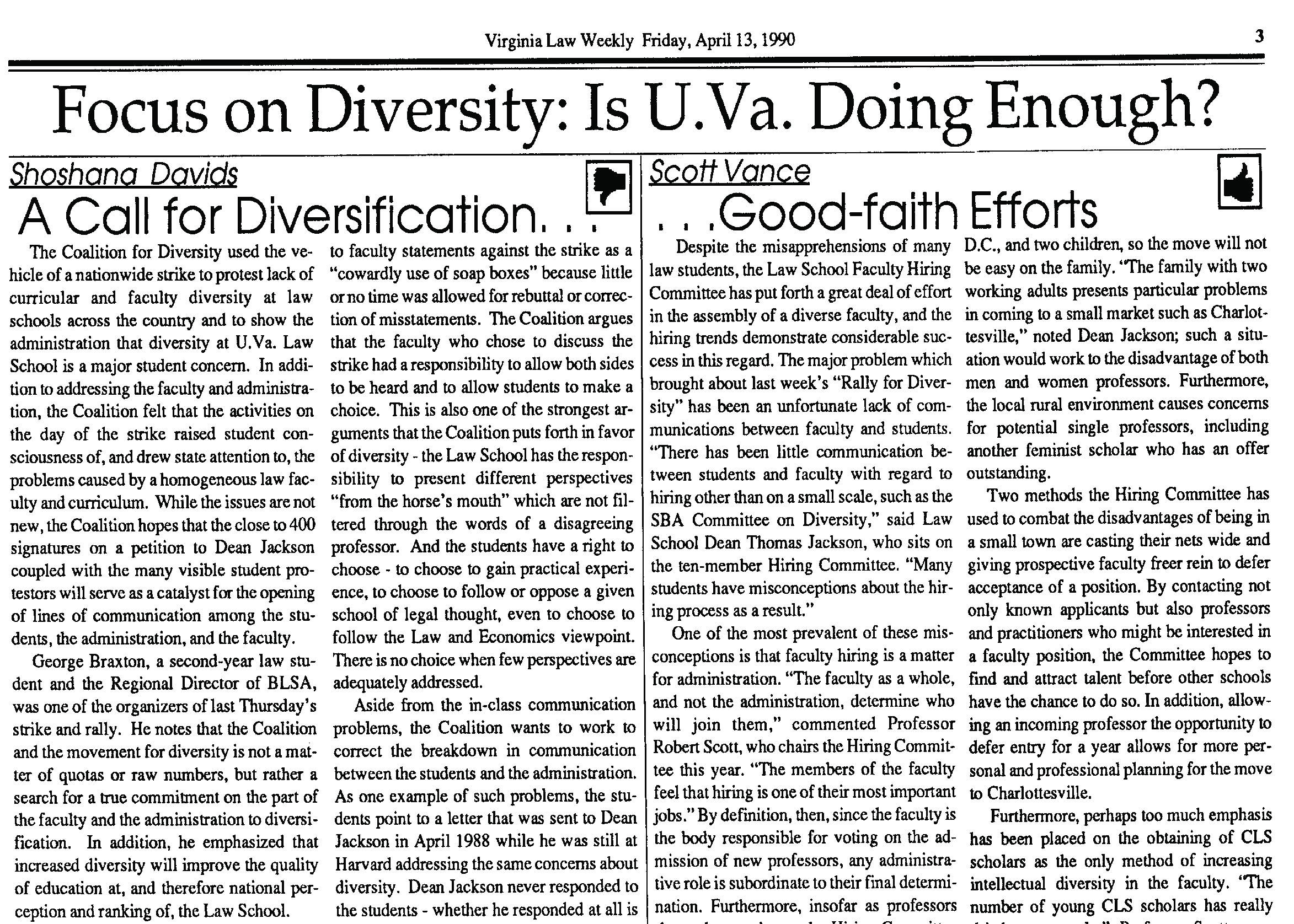

The 1980s: Revitalized Push to Diversify the Faculty

After Larry Gibson’s departure in 1974, a handful of Black professors served on the faculty in part-time teaching positions. In 1977 UVA Law hired its first tenured Black professor, Samuel Thompson, who remained until 1981. In light of the 1977 Supreme Court case The Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, which upheld affirmative action in college admissions, affirmative hiring and student recruitment practices at UVA Law again became a popular talking point. Students and faculty members wrote numerous editorials in the Law Weekly expressing their support of—or concern over—the University’s affirmative action efforts.

On November 11, 1983, BALSA encouraged students to boycott their classes and attend a teach-in, all in an effort to push Law administration to hire Black faculty. Minority recruitment was an ongoing issue at UVA Law, as well as a major agenda item of the National Black American Law Student Association (NBALSA). Melvin “Butch” Hollowell ’84, BALSA Convener, explained to Law Weekly editors at the time that minority student and faculty recruitment was “a national problem which is particularly acute in Virginia.”

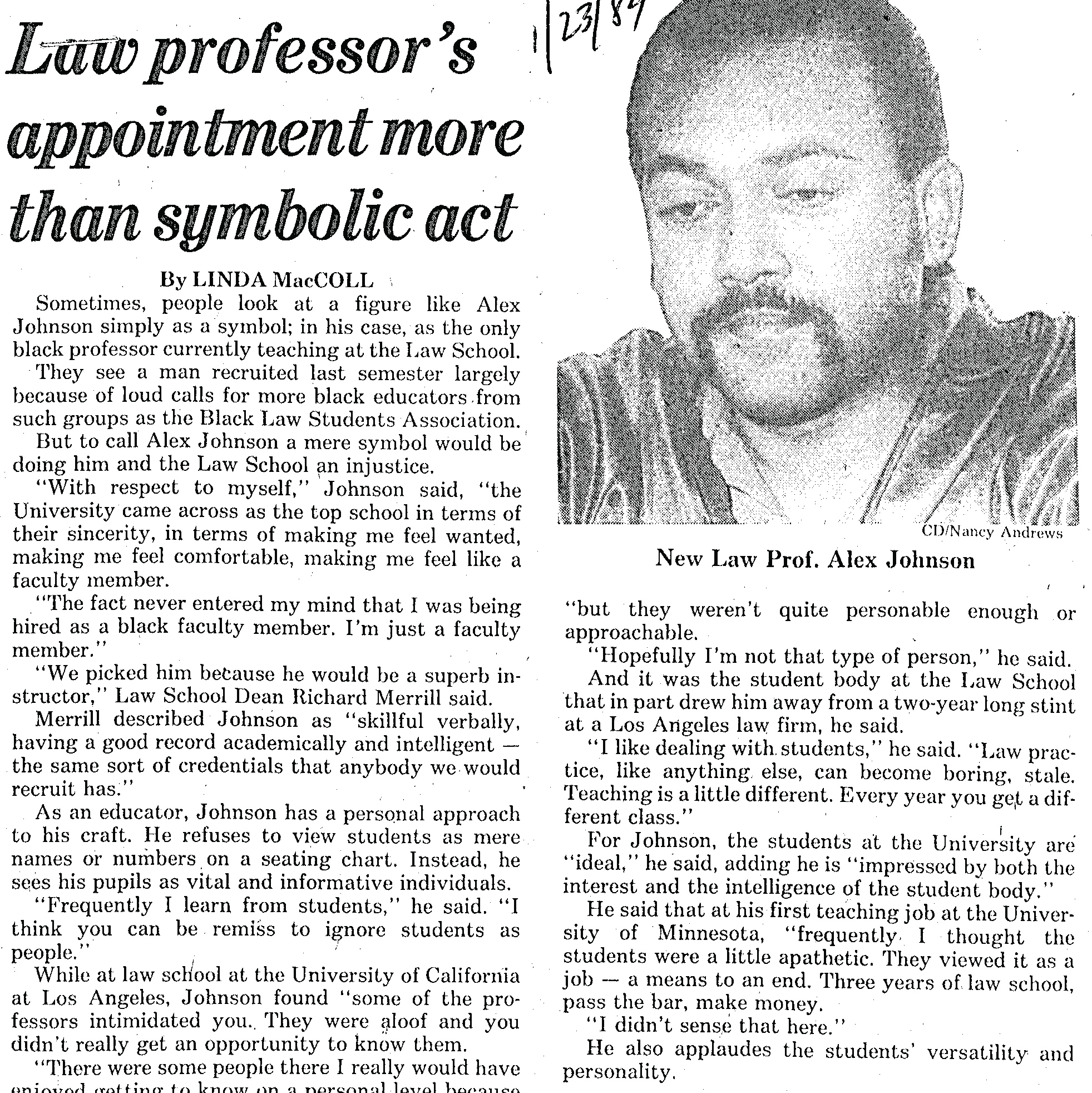

About 200 students and faculty members attended the teach-in, despite the announcement that Alex M. Johnson, Jr., a Black lawyer with experience as a professor and in private practice, had just been hired to the full-time faculty. Among the speakers were Richmond Circuit Judge James B. Sheffield, who taught a seminar course at UVA, Michael Green, President of NBALSA, Dr. Alvin Poussaint of the Harvard Medical School, Ralph Smith, a senior professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Law, and Saad El-Amin, a private attorney from Richmond. Topics were numerous and included practical solutions to faculty hiring, the need for Black role models and mentors, institutionalized racism, and UVA’s responsibility as a state institution to have a diverse faculty and student body that corresponds with the diversity of Virginia’s population.

Dean Richard Merrill later remarked that “The whole program was carried off with great skill and responsibility... everyone who participated should be proud.”

That same year, the NBALSA dropped “American” from the organization’s name to be more inclusive of Black law students of different nationalities. UVA’s chapter followed suit and today is known as the Black Law Students Association (BLSA).

BLSA Addresses Local and International Issues at UVA Law

As the 1980s continued, so did BLSA’s advocacy, particularly around the culture of racial prejudice at the Law School. In 1985, Donald McEachin ’86 penned an editorial to the Law Weekly titled “Grievances,” in which he enumerated BLSA’s ongoing concerns with the faculty and administration. Among them: the limited role of enrolled Black students in the student admissions process, the Law School’s complicity in allowing all-white firms to recruit at UVA, and the recent decision to name the Law School building on North Grounds “Henry Malcolm Withers Hall,” after a man who attended UVA Law in the 1860s and served in the Confederate Army.

In July 2020, Dean Risa Goluboff appointed an ad-hoc committee of alumni/ae, faculty, staff, and students to research Withers and the history behind the naming of the building, following recent initiatives across the University and state to re-contextualize monuments and named buildings. The Board of Visitors voted to remove the name in September 2020.

Amidst ongoing faculty and student recruitment efforts, BLSA pushed Virginia Law’s top journals, the Virginia Journal of International Law (VJIL) and the Virginia Law Review, to adopt affirmative recruitment policies. In 1983, VJIL voted to amend its by-laws to allow race to be considered as a factor in the selection of new members to the editorial board.

“[The decision] is a tremendous step forward for the school, the legal community, and the jurisprudential system as a whole.”

Melvin “Butch” Hollowell ’84

BLSA President 1983-1984

The Law Review proposed a similar by-law amendment the same year, but some members of the board adamantly opposed any affirmative selection criteria, stating that the selection process was “color-blind” and “objective.”

Four years later, in January 1987, the Law Review adopted an affirmative action plan, scheduled for implementation during the spring selection process. Before the plan’s implementation, Dayna Matthew ’87’s note on the Virginia Natural Death Act was published in the Law Review, making her the first Black student to be published by the journal in its 74-year history. Imani Ellis ’88 and Lisa Wilson ’88, then-President and Vice President of BLSA, wrote an editorial to the Law Weekly commending Matthew’s achievement but insisting that it “doesn’t solve everything.”

“The fact that Matthew was extended an invitation without any affirmative action considerations will hopefully have the effect of eradicating the myth of the unqualified black student, while the adoption of an affirmative action plan will simultaneously address the protracted discriminatory impact of the Review’s ‘old policy’ on black students.”

—Imani Ellis ’88 and Lisa Wilson ’88, BLSA President and Vice-President 1986-1987

On her article’s publication, Dayna Matthew ’87 remarked:

“A whole lot more history needs to be made.”

In 2020, more history was made. The Law Review selected the largest Black editorial class in the journal's history (5) and appointed Tiffany Mickel '22 as the journal's first Black editor-in-chief.

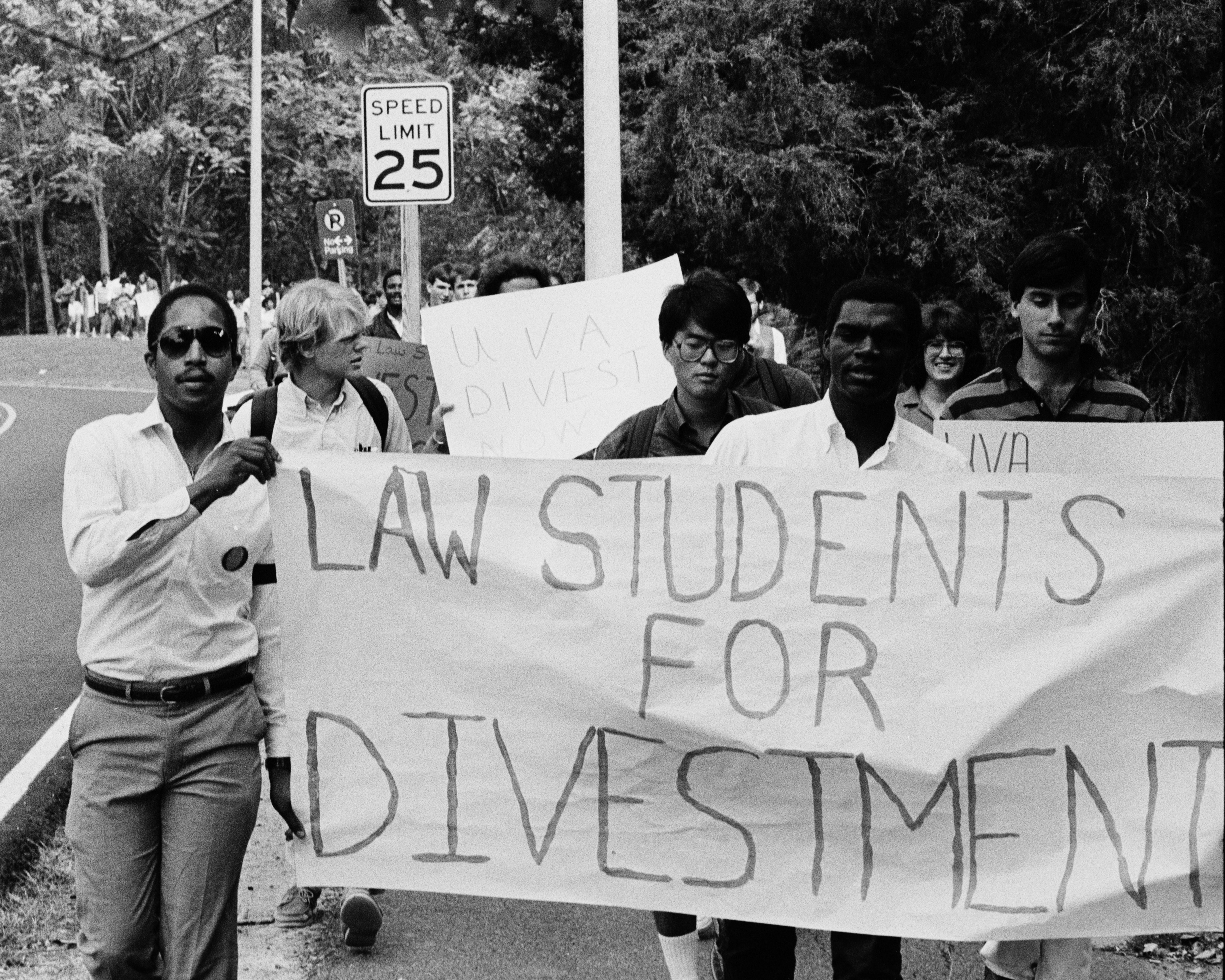

Alongside BLSA’s local activism, the organization added its voice to the numerous Law School and University student groups that pushed UVA to divest from companies that perpetuated apartheid in South Africa. From 1985 until the end of apartheid, BLSA members marched and wrote op-eds to the Law Weekly to bring attention to the issue.

In the 1990s, BLSA continued to address the same issues that plagued members from previous decades, including the lack of diversity on the Law faculty, the desire for greater transparency in the hiring process, and equality of opportunity and treatment for Black students. BLSA members observed that while there were more Black students at UVA than in previous years, these students were disproportionately affected by University disciplinary methods like the Honor System. In 1998, BLSA and the undergraduate Black Student Alliance joined forces to demand that the Honor Committee take steps to ensure minority students were represented both within the Honor Committee and on juries during honor violation cases.

Continuing the Call to Action

The mission of activism with which BLSA was founded fifty years ago remains ever present today. As part of the national reckoning with white supremacy and police violence in the U.S., BLSA held a 2015 “Die-In” at the Law School in protest of the police killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. In a Law Weekly article on the event, BLSA member Raphael Turner ’16 wrote:

“We as a collective have decided that this is not merely a Black or African American issue. The issue of aggressive policing affects all of us as Americans.”

Following the 2020 police murders of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and Sean Reed, BLSA released a statement announcing their solidarity with Black people across the nation and calling for collective action to create a world that is just for all people. Read BLSA’s full statement here.

As BLSA enters its sixth decade, the goals established at BLSA’s inception remain priorities for the organization’s current members. In summer 2020 BLSA called the Law School community to action on issues that have undergirded the organization’s advocacy since 1970. Hire Black faculty. Increase Black student enrollment. Create an inclusive, diverse, and informed Law School environment. Read the organization’s latest Call to Action here.

“In reflecting on BLSA’s role at the Law School over the years,

we are deeply grateful for and inspired

by the resilience, wisdom and strength of all of the BLSA alumni who came before us.”

Allison Burns ’22

BLSA President 2020-2021